“You can’t talk your way out of problems you behave yourself into.”

Real self-respect comes from dominion over self, from true independence. And that’s the focus on Habits 1,2 and 3. Independence is an achievement. Interdependence is a choice only independent people can make. Unless we are willing to achieve real independence, it’s foolish to try to develop human relations skills. We might try. But when the difficult times come, and they will, we won’t have the foundation to keep things together.

The emotional bank account

We all know what a financial bank account is. We make deposits into it and build up a reserve from which we can make withdrawals when we need to. An Emotional Bank Account is a metaphor that describes the amount of trust that’s been built up in a relationship. It’s the feeling of safety you have with another human being.

Six major deposits to build the Emotional Bank Account.

- Understanding the individual

- Attending to the Little Things – the little kindnesses and courtesies are so important. Small discourtesies, little unkindnesses, little forms of disrespect make large withdrawals. In relationships, the little things are the big things.

- Keeping commitments – is a major deposit; breaking one is a major withdrawal.

- Clarifying expectations

- Showing personal integrity – honesty is telling the truth - in other words, conforming our words to reality. Integrity is conforming reality to our words – in other words, keeping promises and fulfilling expectations. This requires an integrated character, a oneness, primarily with self but also with life. One of the most important ways to manifest integrity is to be loyal to those who are not present. In doing so, we build the trust of those who are present. When you defend those who are absent, you retain the trust of those present. Integrity also means avoiding any communication that is deceptive, full of guile, or beneath the dignity of people. “A lie is any communication with intent to deceive,” according to one definition of the word. Whether we communicate with words or behavior, if we have integrity, our intent cannot be to deceive.

- Apologizing sincerely when you make a withdrawal

- The laws of love and the laws of life – rebellion is a know of the heart, not of the mind. The key is to make deposits – constant deposits of unconditional love.

P problems are PC opportunities

In an interdependent situation, every P problem is a PC opportunity – a chance to build the Emotional Bank Accounts that significantly affect interdependent production.

When parents see their children’s problems as opportunities to build relationships instead of as negative, burdensome irritations, it totally changes the nature of parent-child interaction. Parents become more willing, even excited, about deeply understanding and helping their children. When a child comes to them with a problem, instead of thinking, “Oh no! Not another problem!” their paradigm is, “Here is a great opportunity for me to really help my child and to invest in our relationship.” Many interactions change from transactional to transformational, and strong bonds of love and trust are created as children sense the value parents give to their problems and to them as individuals.

It is impossible to achieve Public Victory with popular “Win/Win negotiation” techniques, “reflective listening” techniques, or “creative problem-solving” techniques that focus on personality and truncate the vital character base.

Habit 4: Think Win/Win

Whether you are the president of a company or the janitor, the moment you step from independence into interdependence in any capacity, you step into a leadership role. You are in a position to influence other people. And the habit of effective interpersonal leadership is to think Win/Win.

There are 6 possibilities:

- Win/Win

- Win/Lose

- Lose/Win

- Lose/Lose

- Win

- Win/Win or No Deal

Five dimensions of Win/Win

The following diagram shows how these five dimensions relate to each other

Now let’s consider each of the five dimensions in turn:

Character: is the foundation of win/win, and everything else builds on that foundation. There are three character traits essential to the win/win paradigm:

1. Integrity

2. Maturity – is the balance between courage and consideration. The ability to express one’s own feelings and convictions balanced with consideration for the thoughts and feelings of others.

3. Abundance mentality – the third character trait essential to win/win is the abundance mentality, the paradigm that there is plenty out there for everybody.

Relationships: from the foundation of character, we build and maintain win/win relationships. The trust, the Emotional Bank Account, is the essence of win/win. The best we can do without trust is compromise; without trust, we lack the credibility for open, mutual learning communication and real creativity.

Agreements: from relationships flow the agreements that give definition and direction to win/win. They are sometimes called performance agreements or partnership agreements, shifting the paradigm of productive interaction from vertical to horizontal, from hovering supervision to self-supervision, from positioning to being partners in success.

In the win/win agreement, the following 5 elements are made very explicit:

1. desired results (not methods) identify what is to be done and when

2. guidelines specify the parameters (principles, policies, etc) within which results are to be accomplished.

3. resources identify the human, financial, technical, or organizational support available to help accomplish the results.

4. accountability sets up the standards of performance and the time of evaluation.

5. consequences specify – good and bad, natural and logical – what does and will happen as a result of evaluation.

Creating win/win performance agreements requires a vital paradigm shift. The focus is on results, not methods. Most of us tend to supervise methods.

When a boss becomes the first assistant to each of his subordinates, he can greatly increase his span of control. Entire levels of administration and overhead can be eliminated. Instead of supervising six or eight, such a manager can supervise twenty, thirty, fifty, or more.

In win/win performance agreements, consequences become the natural or logical result of performance rather than a reward or punishment arbitrarily handed out by the person in charge.

There are basically four kinds of consequences (rewards and penalties) that management or parents can control – financial, psychic, opportunity, and responsibility. Financial consequences include such things as income, stock options, allowances, or penalties. Psychic or psychological consequences include recognition, approval, respect, credibility, or the loss of them. Unless people are in survival mode, psychic compensation is often more motivating than financial compensation. Opportunity includes training, development, perks, and other benefits. Responsibility has to do with scope and authority, either of which can be enlarged or dismissed. Win/win agreements specify consequences in one or more of those areas and the people involved know it up front.

Win/win agreements are tremendously liberating. But as the product of isolated techniques, they won’t hold up. Even if you set them up in the beginning, there is no way to maintain them without personal integrity and a relationship of trust.

Systems: For win/win to work, the systems have to support it. The training system, the planning system, the communication system, the budgeting system, the information system, the compensation system – all have to be based on the principle of win/win.

Processes: There’s no way to achieve win/win ends with win/lose or lose/win means. You can’t say “You’re going to think win/win, whether you like it or not.” So the question becomes how to arrive at a win/win solution.

Roger Fisher and William Ury, two Harvard law professors, have done some outstanding work in what they call the “principled” approach versus the “positional” approach to bargaining in their tremendously useful and insightful book, “Getting to Yes”. Although the words win/win are not used, the spirit and underlying philosophy of the book are in harmony with the win/win approach.

They suggest that the essence of principled negotiation is to separate the person from the problem, to focus on interests and not on positions, to invent options for mutual gain, and to insist on objective criteria – some external standard or principle that both parties can buy into.

4 steps process:

1. See the problem from the other point of view. Really seek to understand and to give expression to the needs and concerns of the other party as well as or better than they can themselves.

2. Identify the key issues and concerns (not positions) involved

3. Determine what results would constitute a fully acceptable solution

4. Identify possible new options to achieve those results.

Win/win is the only alternative

Win-lose is counterproductive, competitive, and full of pride. In the words of C.S. Lewis, “Pride gets no pleasure out of having something, only out of having more of it than the next man … It is the comparison that makes you proud: the pleasure of being above the rest.”

Lose-win doesn’t work, either. It’s the doormat syndrome: “Wipe your feet on me. Everyone else does.”

Win-win is the only practical alternative.

Yet, some will say that win-win is soft and you’ll get your lunch eaten if you try it in difficult business situations.

Habit 5: seek first to understand, then to be understood

Empathic listening: involves a very deep paradigm shift. We typically seek first to be understood. Most people do not listen with the intent to understand; they listen with the intent to reply. They’re either speaking or preparing to speak. They’re filtering everything through their own paradigms, reading their autobiography into other people’s lives.

“Oh, I know exactly how you feel!”

“I went through the very same thing. Let me tell you about my experience.”

They’re constantly projecting their own home movies onto other people’s behavior. They prescribe their own glasses for everyone with whom they interact.

If they have a problem with someone – a son, a daughter, a spouse, an employee – their attitude is, “That person just doesn’t understand.”

When another person speaks, we’re usually “listening” at one of 5 levels.

1. We may be ignoring another person, not really listening at all.

2. We may practice pretending. “Yeah, Uh-huh. Right.”

3. We may practice selective listening, hearing only certain parts of the conversation. We often do this when we’re listening to the constant chatter of a preschool child.

4. Or we may even practice attentive listening, paying attention, and focusing energy on the words that are being said.

5. Empathic listening – not referring to “active” listening or “reflective” listening, which basically involves mimicking what another person says. That kind of listening is skill-based, truncated from character and relationships, and often insults those “listened” to in such a way. It is also essentially autobiographical. If you practice those techniques, you may not project your autobiography in the actual interaction, but your motive in listening is autobiographical. You listen with reflective skills, but you listen with intent to reply, to control, to manipulate. Empathic listening means listening with the intent to understand.

Empathic (from empathy) listening gets inside another person’s frame of reference. You look out through it, you see the world the way they see the world, you understand their paradigm, you understand how they feel.

Empathy is not sympathy. Sympathy is a form of agreement, a form of judgment. And it is sometimes the more appropriate emotion and response. But people often feed on sympathy. It makes them dependent. The essence of empathic listening is not that you agree with someone; it’s that you fully, and deeply understand that person, emotionally as well as intellectually.

Empathic listening is, in and of itself, a tremendous deposit in the Emotional Bank Account.

This is one of the greatest insights in the field of human motivation: Satisfied need to not motivate. It’s only the unsatisfied need that motivates. Next to physical survival, the greatest need of a human being is psychological survival – to be understood, to be affirmed, to be validated, to be appreciated. When you listen with empathy to another person, you give that person psychological air. After that vital need is met, you can then focus on influencing or problem-solving. This need for psychological air impacts communication in every area of life. When it comes right down to it, other things being relatively equal, the human dynamic is more important than the technical dimensions of the deal.

Empathic listening is also risky. It takes a great deal of security to go into a deep listening experience because you open yourself up to be influenced. You become vulnerable. It’s a paradox, in a sense, because to have influence, you have to be influenced. That means you have to really understand.

That’s why Habits 1,2 and 3 are so foundational. They give you the changeless inner core, the principal center, from which you can handle the more outward vulnerability with peace and strength.

Four autobiographical responses

Because we listen autobiographically, we tend to respond in one of 4 ways:

1. we evaluate – we either agree or disagree;

2. we probe – we ask questions from our own frame of reference;

3. we advise – we give counsel based on our own experience;

4. we interpret – we try to figure people out, to explain their motives, and their behavior, based on our own motives and behavior.

These responses come naturally to us. We are deeply scripted in them; we live around models of them all the time. But how do they affect our ability to really understand?

Probing is playing twenty questions. It’s autobiographical, it controls, and it invades. It’s also logical, and the language of logic is different from the language of sentiment and emotion. You can play twenty questions all day and not find out what’s important to someone. Constant probing is one of the main reasons parents do not get close to their children.

“How’s it going, son?”

“Fine.”

“Well, what’s been happening lately?”

“Nothing.”

“So what’s exciting in school?”

“Not much.”

“And what are your plans for the weekend?”

“I don’t know.”

You can’t get him off the phone talking with his friends, but all he gives you are one- and two-word answers. Your house is a motel where he eats and sleeps, but he never shares, never opens up.

Let’s study what might be typical communication between a father and his teenage son. Look at the father’s words in terms of the four different responses we have just described.

“Boy, Dad, I’ve had it! School is for the birds!”

“What’s the matter, son?” (probing).

“It’s totally impractical. I don’t get a thing out of it.”

“Well, you just can’t see the benefits yet, son. I felt the same way when I was your age. I remember thinking what a waste some of the classes were. But those classes turned out to be the most helpful to me later on. Just hang in there. Give it some time.” (advising)

“I’ve given it ten years of my life! Can you tell me what good ‘x plus y’ is going to be to me as an auto mechanic?”

“An auto mechanic? You’ve got to be kidding” (evaluating).

“No, I’m not. Look at Joe. He’s quit school. He’s working on cars. And he’s making lots of money. Now that’s practical.”

“It may look that way now. But several years down the road, Joe’s going to wish he’d stayed in school. You don’t want to be an auto mechanic. You need an education to prepare you for something better than that” (advising).

“I don’t know. Joe’s got a pretty good setup.”

“Look, son, have you really tried?” (probing, evaluating).

“I’ve been in high school for two years now. Sure I’ve tried. It’s a waste.”

“That’s a highly respected school, son. Give them a little credit” (advising, evaluating).

“Well, the other guys, feel the same way I do.”

“Do you realize how many sacrifices your mother and I have made to get you where you are? You can’t quit when you’ve come this far” (evaluating)

“I know you’ve sacrificed, Dad. But it’s just not worth it.”

“Look, maybe if you spend more time doing your homework and less time in front of the TV…” (advising, evaluating).

“Look, Dad. It’s just no good. Oh … never mind! I don’t want to talk about this anyway.”

Obviously, his father was well-intended. Obviously, he wanted to help. But did he even begin to really understand?

The skills, the tip of the iceberg of empathic listening, involve 4 development stages:

1. The first and least effective is to mimic content.

This is the skill taught in “active” or “reflective” listening. Without the character and relationship base, it is often insulting to people and causes them to close up. It is, however, a first-stage skill because it at least causes you to listen to what’s being said.

You have essentially repeated back the content of what was being said. You haven’t evaluated or probed advised or interpreted. You’ve at least shown you’re paying attention to his words. But to understand, you want to do more.

2. rephrase the content.

It’s a little more effective, but it’s still limited to the verbal communication. This time, you’ve put his meaning into your own words. Now you’re thinking about what he said, mostly with the left side, the reasoning, logical side of the brain.

3. reflect feeling

“Boy, Dad, I’ve had it! School is for the birds!”

“You’re feeling really frustrated.”

Now you’re not paying as much attention to what he’s saying as you are to the way he feels about what he’s saying.

4. includes both the second and the third. You rephrase the content and reflect the feeling. Frustration is the feeling; school is the content. You’re using both sides of your brain to understand both sides of his communication.

Let’s redo the initial dialogue now:

“Boy, Dad, I’ve had it! School is for the birds!” (I want to talk with you, to get your attention.)

“You’re really frustrated about school.” (that’s right! That’s how I feel.)

“I sure am. It’s totally impractical. I’m not getting a thing out of it.”

“You feel like school’s not doing you any good.” (Let me think – is that what I mean?)

“Well, yeah. I’m just not learning anything that’s going to help me. I mean, look at Joe. He’s dropped out of school and he’s working on cars. He’s making money. Now that’s practical.”

“You feel that Joe really has the right idea.” (Well…)

“Well, I guess he does in a way. He’s really making money now. But in a few years, I bet he’ll probably be ticked off at himself.”

“You think Joe’s going to feel he made the wrong decision.”

“He’s got to. Just look at what he’s giving up. I mean, if you don’t have an education, you just can’t make it in this world.”

“Education is really important.”

“Oh, yeah! I mean, if you don’t have a diploma, if you can’t get jobs or go to college, what are you going to do? You’ve just got to get an education.”

“It’s important to your future.”

“It is. And … you know what? I’m really worried. Listen, you won’t tell Mom, will you?”

“You don’t want your mother to find out.”

“Well, not really. Oh, I guess you can tell her. She’ll probably find out anyway. Look, I took this test today, this reading test. And, Dad, they said I’m reading on a fourth-grade level. Fourth grade! And I’m a junior in high school!”

By seeking first to understand, the father has just turned a transactional opportunity into a transformation opportunity. Instead of interacting on a surface, get-the-job-done level of communication, he has created a situation in which he can now have a transforming impact, not only on his son but also on the relationship. By setting aside his own autobiography and really seeking to understand, he has made a tremendous deposit in the Emotional Bank Account and has empowered his son to open, layer upon layer, and get to the real issue.

Now father and son are on the same side of the table looking at the problem, instead of on opposite sides looking across at each other. The son is opening his father’s autobiography and asking for advice.

Even as the father begins to counsel, however, he needs to be sensitive to his son’s communication. As long as the response is logical, the father can effectively ask questions and give counsel. But the moment the response becomes emotional, he needs to go back to empathic listening.

“Well, I can see some things you might want to consider.”

“Like what, Dad?”

“Like getting some special help with your reading. Maybe they have some kind of tutoring program over at the tech school.”

“I’ve already checked into that. It takes two nights and all day Saturday. That would take so much time!”

Sensing emotion in that reply, the father moves back to empathy.

“That’s too much of a price to pay.”

“Besides, Dad, I told the sixth grades I’d be their coach.”

“You don’t want to let them down.”

“But I’ll tell you this, Dad. If I really thought that tutoring course would help, I’d be down there every night. I’d get someone else to coach those kids.”

“You really want to help, but you doubt if the course will make a difference.”

“Do you think it would, Dad?”

The son is once more open and logical. He’s opening his father’s autobiography again. Now the father has another opportunity to influence and transform.

There are times when transformation requires no outside counsel. Often when people are really given the chance to open up, they unravel their own problems and the solutions become clear to them in the process.

Should you use Habit 5 all the time?

No. There is a time and a place for Empathic Listening. Use Empathic Listening when the topic is important, sensitive, or really personal, like when a colleague needs career advice, or if you’re having a communication problem with a loved one. These conversations take time and can’t be rushed. A good rule of thumb is to use empathy any time emotions are high. You don’t need to do it in casual conversation or everyday small talk. If somebody comes up to you and says, “Where’s the bathroom? I gotta go real bad,” you don’t need to say, “So if I understand you correctly, you really need to go.”

Why is this habit so hard?

If you struggle with this habit, you’re in good company. “It’s hard to listen when you know you’re right.”

University of California professor Dacher Keltner coined the term the “power paradox” to describe how leaders gain influence through empathy and other practices that serve others, but lose those skills as they gain influence and power. In fact, the further you go up the ladder, the less empathy leaders tend to have.

We increasingly communicate via text and email. Does that change anything about this habit?

Yes, it definitely does. Let’s use this example: someone gets upset and sends a pointed email. The other person writes back a novel. Then they start copying people…and more people. And I’m like “For crying out loud, just get on the phone and talk it through.”

The use of technology strips out the tone of voice and facial expressions that help us empathize. So anytime you’re dealing with an important, emotional issue, do not email or text. At some point, meet face-to-face or at least talk it out over the phone. An emoji just isn’t going to cut it. 😁

What if you can’t get to a resolution through Empathic Listening?

Resolving the conflict isn’t actually the goal of empathic listening – understanding is.

Sometimes when I try Empathic Listening, the other person feels like I’m using a technique.

People will sense immediately if Empathic Listening isn’t genuine. You need to have good intent, not just the skill. When facing a relationship conflict, most people keep working on the Public Victory. As we learned from the example with the son and father, many relationship challenges can only be solved by winning the Private Victory first. You have to go back to Habit 1 and use your self-awareness, conscience, imagination, and independent will to get clear on your motives. Use Habit 2 to envision what you want to do differently. And then make it happen through Habit 3. Seeking first to understand another person makes you vulnerable because you may learn some things that are threatening to you. To genuinely practice Habit 5, you may need the emotional security that comes from first winning the Private Victory.

Habit 6: Synergize

“That which is most personal is most general.” The more authentic you become, the more genuine your expression, particularly regarding personal experiences and even self-doubts, the more people can relate to your expression, and the safer it makes them feel to express themselves. That expression in turn feeds back on the other person’s spirit, and genuine creative empathy takes place, producing new insights and learning and a sense of excitement and adventure that keeps the process going. People then begin to interact with each other almost in half sentences, sometimes incoherent, but they get each other’s meanings very rapidly.

The attitude was “If a person of your intelligence competence and commitment disagrees with me, then there must be something to your disagreement that I don’t understand, and I need to understand it. You have a perspective, a frame of reference I need to look at.”

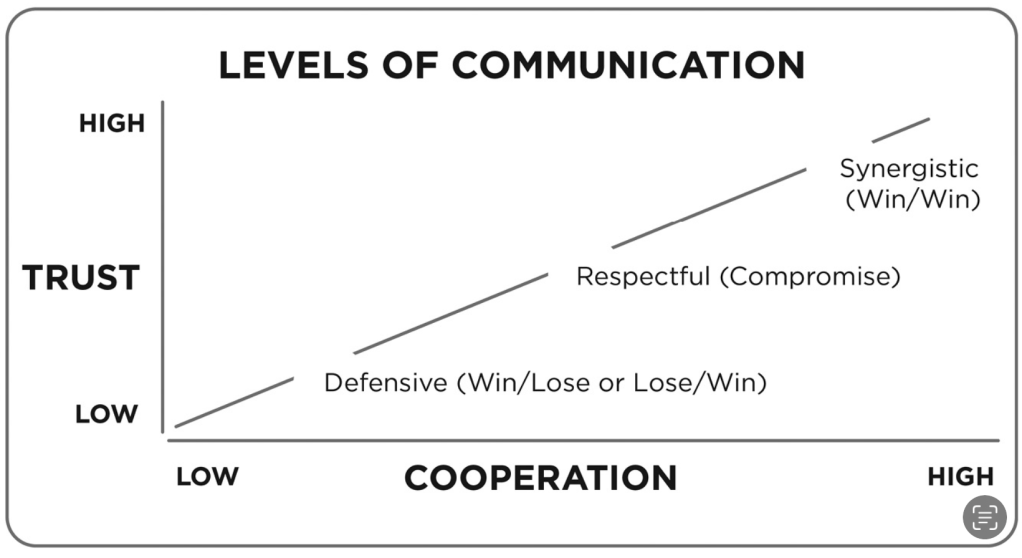

The following diagram illustrates how closely trust is related to different levels of communication.

Negative synergy

The problem is that highly dependent people are trying to succeed in an interdependent reality. They’re either dependent on borrowing strength from position power and they go to Win/Lose, or they’re dependent on being popular with others and they go for Lose/Win. They may talk Win/Win technique, but they don’t really want to listen; they want to manipulate. And synergy can’t thrive in that environment.

“Manage from the left, lead from the right”

– the left side of the brain wants: facts, figures, specifics, parts

– the right side of the brain: deals with sense, the whole, the relationship between the parts, images, intuitive feelings

Example from a couple dealing with their issues:

Observer of the dialogue between the spouse and husband intervened and said:

“Is this kind of how it goes in your relationship?”

“Every day” he replied.

“It’s the story of our marriage.” she sighed.

Observer looked at the two of them and the thought crossed his mind that they were two half-brained people living together.

“Do you have any children?” the observer asked.

“Yes, two.”

“Really? How did you do it?”

“What do you mean how did we do it?”

“You were synergistic! One plus one usually equals two. But you made one plus one equal four. Now that’s synergy. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts. So how did you do it?”

“You know how we did it,” he replied.

“You must have valued the differences!” observed exclaimed.

Valuing the differences

Valuing the differences is the essence of synergy – the mental, the emotional, and the psychological differences between people. And the key to valuing those differences is to realize that all people see the world, not as it is, but as they are.

If I think I see the world as it is, why would I want to value the differences? Why would I even want to bother with someone who’s “off track”? My paradigm is that I am objective; I see the world as it is. Everyone else is buried by the minutiae, but I see the larger picture. That’s why they call me a supervisor – I have supervision.

The truly effective person has the humility and reverence to recognize his own perceptual limitations and to appreciate the rich resources available through interaction with the hearts and minds of other human beings. That person values the differences because those differences add to his knowledge, and to his understanding of reality. When we’re left to our own experiences, we constantly suffer from a shortage of data.

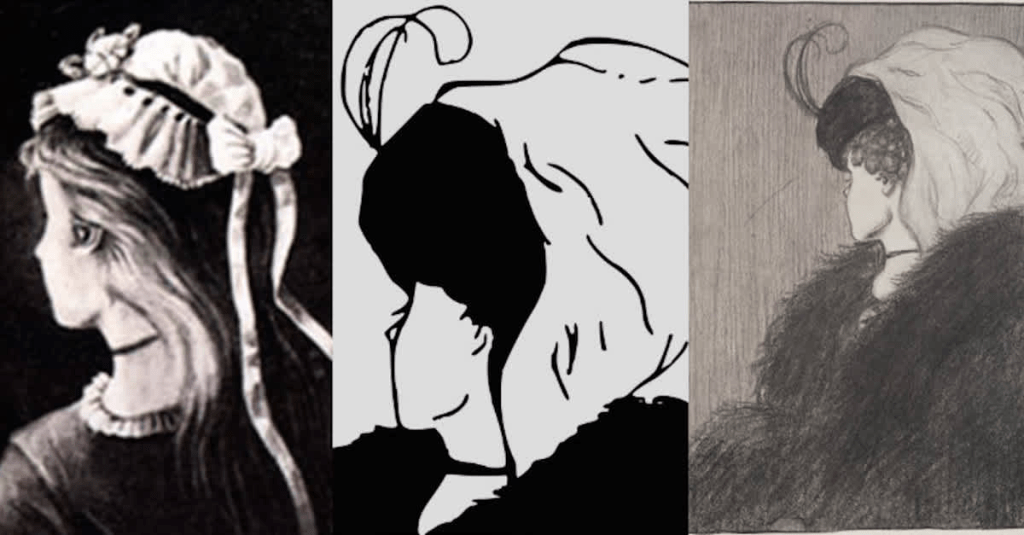

It is logical that two people can disagree and that both can be right? It’s not logical; it’s psychological. And it’s very real. You see the young lady; I see the old woman. We’re both looking at the same picture, and both of us are right. We see the same black lines, the same white spaces. But we interpret them differently because we’ve been conditioned to interpret them differently.

So when you become aware of the difference in our perceptions, I say, “Good! You see it differently! Help me see what you see.”

If two people have the same opinion, one is unnecessary. It’s not going to do me any good at all to communicate with someone else who sees only the old woman also. I don’t want to talk, to communicate, with someone who agrees with me; I want to communicate with you because you see it differently. I value the difference.

Force field analysis

In an interdependent situation, synergy is particularly powerful in dealing with negative forces that work against growth and change.

Sociologist Kurt Lewin developed a “Force Field Analysis” model in which he described any current level of performance or being as a state of equilibrium between the driving forces that encourage upward movement and the restraining forces that discourage it. Although you cannot control the paradigms of others in an interdependent interaction or the synergistic process itself, a great deal of synergy is within your Circle of Influence. Your own internal synergy is completely within the circle. You can respect both sides of your own nature – the analytical side and the creative side. You can value the difference between them and use that difference to catalyze creativity.

You can be synergistic within yourself even in the midst of a very adversarial environment. You don’t have to take insults personally. You can sidestep negative energy; you can look for the good in others and utilize that good, as different as it may be, to improve your point of view and to enlarge your perspective.

You can value the difference in other people. When someone disagrees with you, you can say, “Good! You see it differently.” You don’t have to agree with them; you can simply affirm them. And you can seek to understand.

Application suggestions:

- Think about a person who typically sees things differently than you do. Consider ways in which those differences might be used as stepping-stones to third-alternative solutions. Perhaps you could seek out his or her views on a current project or problem, valuing the different views you are likely to hear.

- Make a list of people who irritate you. Do they represent different views that could lead to synergy if you had greater intrinsic security and valued the difference?

- Identify a situation in which you desire greater teamwork and synergy. What conditions would need to exist to support synergy? What can you do to create those conditions?

- The next time you have a disagreement or confrontation with someone, attempt to understand the concerns underlying that person’s position. Address those concerns in a creative and mutually beneficial way.

Getting to synergy

Synergy doesn’t just happen. You have to get there. If you are not sure where to start, follow this simple process:

- Define the problem or opportunity

- Their way (seek first to understand the ideas of others)

- My way (seek to be understood by sharing your ideas)

- Brainstorm (create new options and ideas)

- Highway (find the best solution)

Pingback: The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People – Part four: Renewal | alin miu